SOMETHING FOR NOTHING

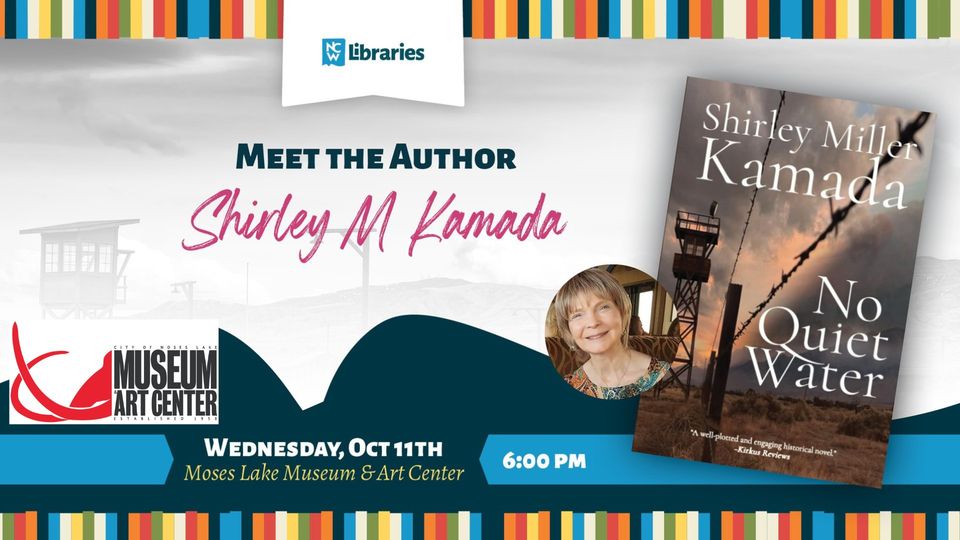

My historical novel was initially titled For the Duration. Later, Suddenly, Flyer. That became, And Then Flyer. Finally, the book found its title and was published as No Quiet Water. The story, which follows the experiences of a Japanese American family forced from their home during WWII, was in development for ten years.

I knew from the beginning that the main character would have my husband’s personality and his real name, Fumio. The rest of the story revealed itself slowly. One morning I offered to read a chapter for my husband, who goes by Jimmy. Sitting beside him on the couch, the first dozen manuscript pages in hand, I explained, “In the story, it’s 1941. November. Fumio and his best friend Zachary are ten years old.”

Jimmy was willing, so I read:

“His schoolbag over his shoulder, Fumio went from the Miyota’s kitchen out onto the porch. ‘Hey, Flyer!’ The dog looked up, met his eyes, and bumped Fumio’s knee with his muzzle. ‘We’re on foot today until we get to Zachary’s house, so we’d better get moving!’

“At the Whitlock home, Zachary came out the door. ‘Morning, Fumio! I didn’t think it would take you two days to get your bike’s front fender fixed.’

“‘Well, Father reminded me that cleaning the truck’s air filter was more important than repairing my bicycle. And maybe it would help me remember that charging full speed around a corner on a gravel road isn’t a good idea.’ Fumio swung up on the back of Zachary’s bike, keeping his weight off the carrier.”

I glanced toward my husband, who was frowning. I read on.

“Near the schoolhouse, Fumio called, ‘Go back now, Flyer.’ The dog barked once then turned toward home.”

Jimmy offered no comment. Still, that frown. The scene was straightforward. I thought he’d approve. I laid down the pages and asked,

“So, is there a problem?”

“He wouldn’t do that.”

“Who wouldn’t do what?”

“Fumio. He wouldn’t ride on the back of Zachary’s bike.”

“But Zachary is his best friend.”

“Fumio wouldn’t bum a ride. He wouldn’t ride on the back of anyone’s bike.

“But his own bike needs work!”

“He’d walk.”

I rewrote three chapters. It was Zachary’s bicycle that was “wounded.” He shared Fumio’s bike on the ride to school. I remained mindful of that key understanding while completing the Miyotas’ story.

Fumio Miyota was required to grasp the social expectations of both the Japanese and American cultures, as well as acknowledge differences in what behaviors were acceptable when with others of his age, versus in the presence of his elders. And, in the camp where his family was interned—incarcerated, without charge of wrongdoing—he knew he must maintain an awareness of the military presence.

My husband’s parents were born in Seattle. The Kamada family was, and is, very American. But traditional Japanese cultural injunction was strong: One does not borrow. One does not make personal use of something one does not own. And one does not, ever, accept something for nothing.