Why Kishōtenketsu?

We plan. We work. We cry. We exult. We laugh.

This is life.

The most popular narrative arc in the United States is undeniably the hero’s journey. While writing my historical novel, No Quiet Water, I found that the story did not fit this archetype. I drew a wall-size representation of the well-known form and studied it, considering how to rework my story to make it fit. Then—serendipity!—I stumbled on a description of a centuries-old literary form that originated in China but eventually came to belong to Japan. Today it is widely known as kishōtenketsu.

Kishōtenketsu has been called, “the story with a conflict-less plot.” Instead, the plot, or meaning, is presented much as are pieces of a puzzle or as a riddle, the solution to which is only realized at the end.

Ah-hah! I recognized immediately I was writing a story that followed its own path, a story that might reveal its meaning in the final scene.

Sharing an early draft of my manuscript for an in-progress-read, I was asked, “Why choose a form that is unfamiliar to most Americans rather than the traditional hero archetype?” The concern was, would this story, when it became a book, find a place on the shelves of homes and libraries?

Modern readers of the Western tradition have also encountered, among other literary structures, The Three Act Structure, and Blake Snyder’s “Save the Cat.” In these tales, characters brave enormous obstacles, struggle against great odds and, at the apex of the story’s action, harvest a bumper crop or lose the farm; gain celebrity or bear ignominy—often, stare down death while grasping at life. If life prevails, then, resolution. Triumph. This fulfills expectations for us, as writers and readers, film producers and theater goers.

Kishōtenketsu, though, progresses differently.

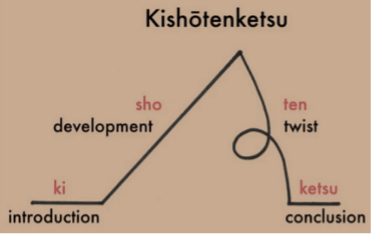

Author Jimmy Kindree, in his essay, “Words Like Trees: Kishōtenketsu”* explains, “Kishōtenketsu, [which is] a compound word of the four elements that constitute this structure, prescribes an engaging story without Western ideas of conflict. Put simply, the structure works like this:

- Ki: exposition, in which a setting and characters are introduced.

- Shō: development, in which the writer expands upon the Ki.

- Ten: turn or twist, in which a new, seemingly unrelated or mysterious element appears. We can think of this as the narrative introducing a kind of chaos into an up-to-now orderly world.

- Ketsu: reconciliation, in which we see how the Ki, Shō, and Ten all fit together, forming a congruous whole.”

A similar graphic is referenced in Jimmy Kindree’s essay, “Words Like Trees: Kishōtenketsu.” The design is found in many places online, but not cited.

Author Kindree writes, “I think this is fascinating. The structure bases reader engagement on their desire to see the two dissonant parts of the story reconciled. . . . While conflict certainly exists it is not responsible for moving the story along as it does in a three-act story.”

Writers know that the hero’s journey template offers a measure of predictability. It’s true that stories such as these have proven to be “solid sellers” in the publishing world.

Why, then, choose kishōtenketsu? Life does not always allow us to choose our fight. Life is bigger than that. Don’t we all dream of coasting to a lovely conclusion because we are, after all, good people? But life seldom works that way. A fight might be thrust upon us. And victory, I am sorry to say, does not always follow.

We need stories that reflect life as it is, stories that give us examples of problem-solving and hoped-for resolutions that might not end on the last page of a book. Life goes on and, like it or not, we must usually drag some baggage with us.

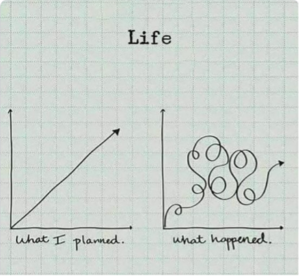

*Life, unrevised, gives few examples of satisfying stories. Even daily news reportage is revised. A director chooses what event to feature, how to describe it, at what point in real time to begin filming, and when to call, “Cut!”

But in creating story— creating art—is kishōtenketsu an authentic, viable structure? Is it an affectation? An oddity?

I have learned that in recent years the form has drawn broader attention as writers and publishers work to present a more inclusive body of literature, readers search out and recommend favorites, and educators reinforce what is valuable in diverse art forms. Kishōtenketsu has found its place in the sun. It is authentic and has withstood the test of time.

Returning to the earlier question: Why would a writer—why would I, in writing No Quiet Water—specifically choose to work in this form?

Kishōtenketsu honors curiosity.

In creating a story the writer begins with raw material, an event, an imagining, a question—what if? Curiosity is native to the creation of a story. And, I believe, curiosity is the clarion call that moves a reader to pick up a book, or an e-reader, and dive into a story.

In the matter of theme, this story form inclines not toward conflict, rather, a problem solved or managed through the main character’s personal development. Managed. Not necessarily vanquished. We cannot vanquish every problem. After all, aren’t some of our most frustrating problems persons in our life? Persons we love?

Why kishōtenketsu? Is this sort of story engaging? Satisfying? Does it leave the reader wanting more? Yes. Although the tradition is ancient, this story form is current. Relevant. Genuine. As you turn the last page, this sort of story will not dust its hands of you. Nor you of it. The story goes on with you. As in life, you are always on your way somewhere—sometime. What comes next?

~ ~ ~

*Is conflict necessary?: Kishōtenketsu and the conflict-less plot – Words like trees (wordpress.com) Published online with further sources by Jimmy Kindree, January 27, 2019

Note: This sketch, “Life, unrevised,” a bit of ironic humor, is frequently seen on Facebook, but without citation. I’ve searched but haven’t found its provenance. If you know the origin, I hope you’ll share it with me.