“Ichi-ni-san” by Frank Fujii

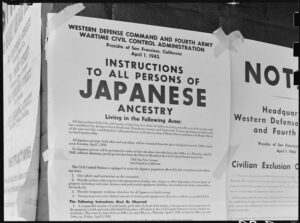

Executive Order 9066, signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, established “military zones” in Washington, Oregon, and California, and gave the U.S. Army authority to remove from those zones all persons of Japanese ancestry, to as little as one-sixteenth percent—approximately 120,000 civilians. Nearly two-thirds were U.S. citizens.

Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement

One-third of those imprisoned were children, babies newborn and yet unborn. Youngsters, teens, collegians, young adults, householders. Farmers, teachers, medical professionals, business owners, commodities brokers. Aging, energetic, keen-minded, health-compromised, fragile.

Two-year-old Yuki Okinaga Hayakawa

Crowded. Confined. Restless. Resigned.

Angry. Hurting. Grief-stricken. Proud.

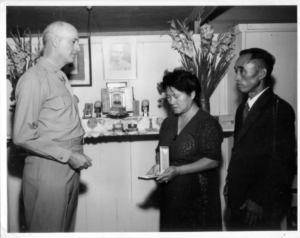

The parents of Pvt. Walter E. Kanaya receive the Silver Star Medal posthumously awarded their son, killed near Bruyeres, France, in October of 1944.

Honolulu, Hawai’i on August 25, 1945.

Misjudged. Misrepresented. Resourceful. Relentless.

Memorial Day services in 1942 at Camp Manzanar, California.

Camp Manzanar, CA

U.S. internment camps were closed in March of 1946. Proof of employment and living arrangements at the intended destination was required. Many who remained in the barracks were aged, many were in ill health. Many had lost everything. Much had been vandalized or stolen. No respite. No home. Nowhere to go. But all were ordered to leave the premises.

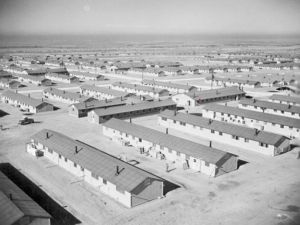

Colorado’s Granada Relocation Center, also known as Camp Amache, 1942.

In December of 1944, President Roosevelt suspended Executive Order 9066, but not until February 19, 1976, was the order officially terminated by President Gerald Ford.

In 1946 the camps were shut down, but not until the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 were individuals of Japanese ancestry allowed to become naturalized U.S. citizens.

In 1980, President Jimmy Carter signed legislation to create the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians to conduct an official governmental study of Executive Order 9066, related wartime orders, and their effects on Japanese Americans in the West and Alaska Natives in the Pribilof Islands.

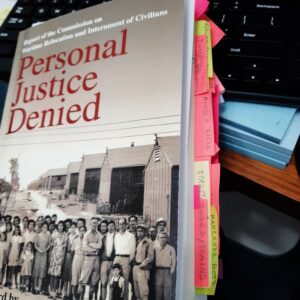

In December of 1982, the CWRIC issued its findings in Personal Justice Denied,* concluding that the incarceration ofJapanese Americans had not been justified by military necessity, and the decision to incarcerate was based on “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” The Commission recommended an official government apology and a redress payment of $20,000 to each of the survivors. A public education fund was established to help ensure this would never happen again.

Not until August 10, 1988, was the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 signed into law by President Ronald Reagan.

On November 21, 1989, President George H. W. Bush signed an appropriation bill authorizing payments to be paid out between 1990 and 1998. Surviving internees began receiving redress payments and letters of apology.

For most, the letters of apology were of greatest importance.

When I was a child, my mother emphasized that an apology was a solemn promise: The wrongdoing will never be repeated.

This year, 2022, marks the 80th observance of The Day of Remembrance.

If as a nation we are to honor the apology, to keep our promise, it is up to us—to each of us—to ensure that such egregious disregard of human rights is never repeated.

We must renew that vow at each sunset if we are to achieve the dream of peace in this world. And at each dawn we must renew that vow, examine our intentions, and walk with integrity.

Originally published in two volumes by the U.S. Government Printing Office in 1982 and 1983.

==//==

About the photographs:

Heading Image One “Ichi-ni-san” Day of Remembrance barbed wire logo created by Frank Fujii. The “ichi-ni-san” logo is composed of the Japanese characters for numbers 1 through 3, representing first, second and third generation Japanese Americans.

Image Two: Records of the War Relocation Authority: Photographs of Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement; public domain.

Image Three: Two-year-old Yuki Okinaga Hayakawa, photographed at Union Station in Los Angeles, waiting for the train to Manzanar. (Note the little purse she carries.) Photographer, Russell Lee, Farm Security Administration, Library of Congress; public domain.

Image Four: Risaku Kanaya and her husband receive the Silver Star Medal posthumously awarded to their son Pvt. Walter E. Kanaya, killed near Bruyeres, France in October of 1944. Honolulu, Hawai’i, August 25, 1945; public domain. Courtesy of the Seattle Nisei Veterans Committee and the U.S. Army.

Image Five: Memorial Day services in 1942 at Camp Manzanar, California. Photo courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration; public domain.

Image Six: Colorado’s Granada Relocation Center, also known as Camp Amache, 1942. Photograph: National Parks Service via the Library of Congress; public domain.

Image Seven: Personal Justice Denied was originally published in two volumes by the U.S. Government Printing Office in 1982 and 1983. Personal Justice Denied. Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. Personal Justice Denied:. Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. Seattle: University of Washington Press and Washington D.C.: Civil Liberties Public Education Fund, 1997.