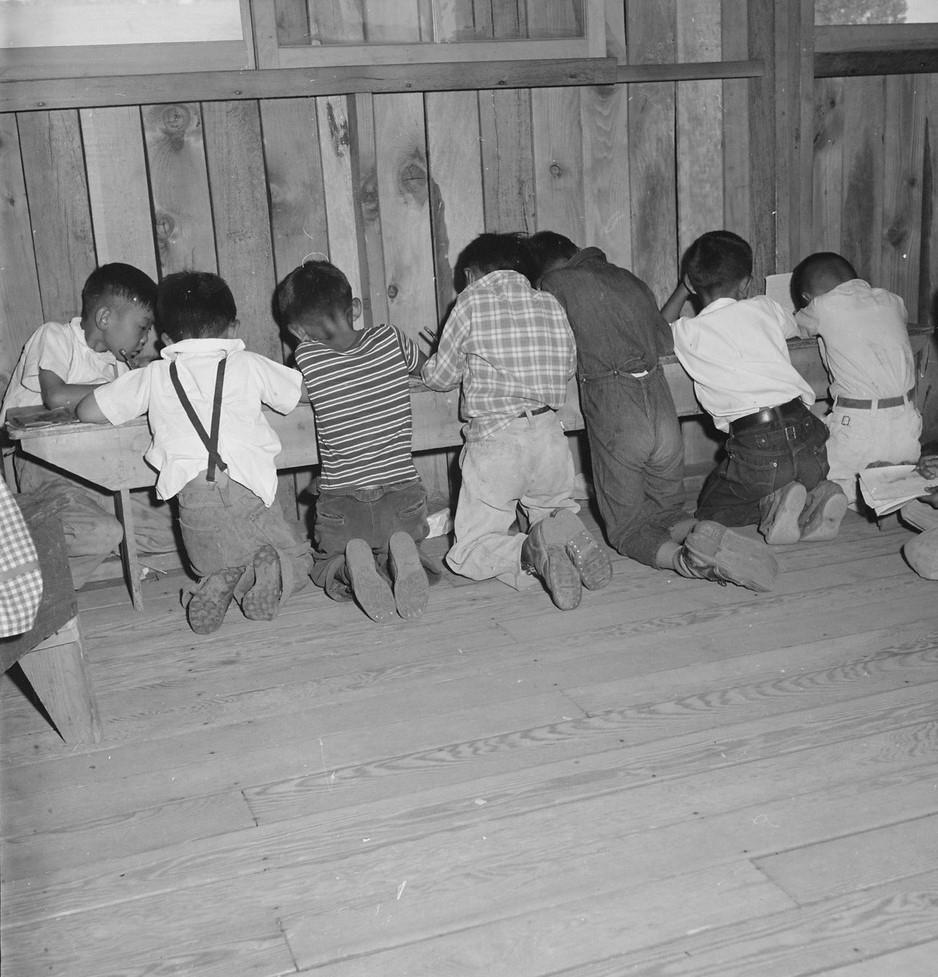

Original WRA caption: Manzanar Relocation Center third-grade students working on their arithmetic lesson at this first volunteer elementary school. School equipment was not yet available at the time this photograph was taken. July 1, 1942.

Photo by Dorothea Lange, courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

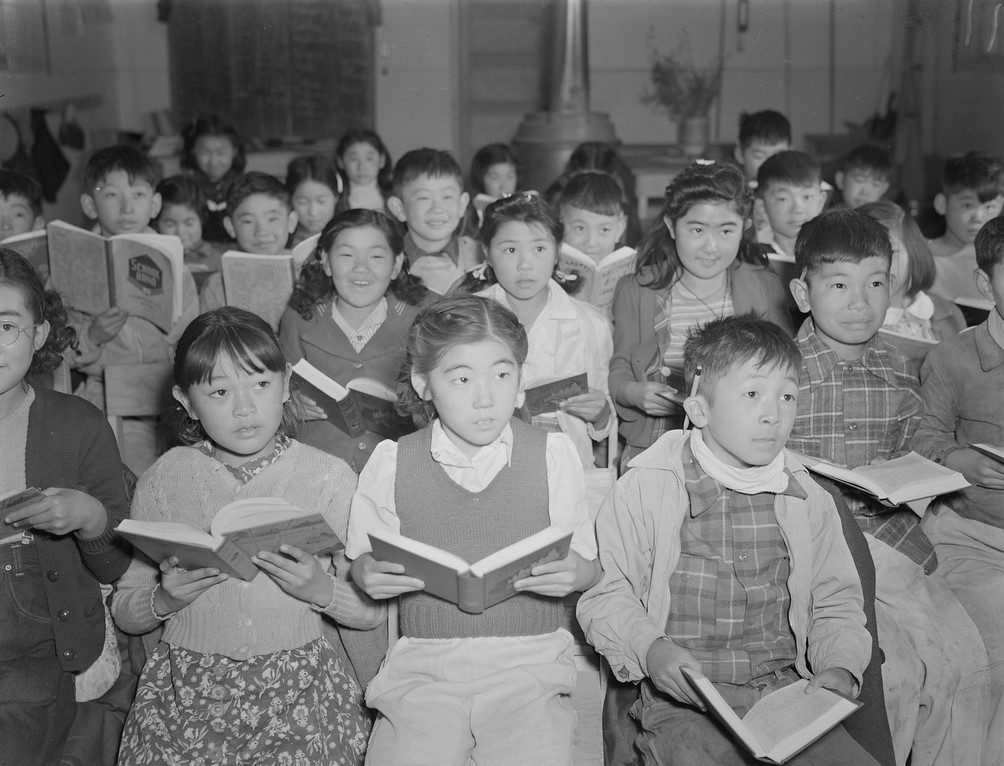

Original WRA Caption: A view in grammar school at relocation center.

Tule Lake concentration camp. November 4, 1942. Photo by Francis Stewart.

Courtesy of the National Records and Archives Administration.

From a dusty railroad car to a dusty chartered bus, to Owens Valley Reception Center, so new it wasn’t finished. The Sierra Range and the Alabama hills backdrop acres of sagebrush, rabbit bush and randomly strewn boulders.

In the foreground, trucks’ engines roar, hammers ring. The smells of diesel fuel and new wood sting nostrils. Sawdust blows in the wind with grit from the denuded landscape, scraped raw by blades of bulldozers.

Adults, wool coats draped across their arms, wear Sunday best—stylish hats, polished shoes. Tags printed with their names and ID numbers hang from strings on shoulders. All move toward military personnel, some who carry bayoneted rifles and some, long knives, sheathed. Others, pens stabbed behind their ears, brandish clipboards, beckon inductees forward, search their possessions and assign cubicles in the vast array of tarpapered barracks.

Inductees. Forcibly removed. Plucked from homes, their known work, careers. Denied their parks and ball fields. Their schools. As if these displaced persons, more than two-thirds of them United States citizens, had been sieved in a filter of humanity and slipped through. Separated and discarded in this desert.

The school year not completed, parents fear children will fall behind. The Wartime Civil Control Administration has no budget, no trained personnel or supplies for schools. In the spring, parents call on nisei, young collegians, to work out a summer school program.

Late summer brings thoughts of their real homes, their real schools. The excitement of the first day of school: Emphatically yellow buses* deliver students to tidy buildings where tile floors gleam under fresh wax. Burnished slates’ chalk trays hold pristine cylinders, eggshell white. Desks in rows are paired with chairs.

This place, now Camp Manzanar, offers none of these.

- No desks. No chairs. No blackboards.

- Textbooks non-existent, not forthcoming.

- Whose responsibility? What county? Which state?

- Base camp in the desert. Base of nowhere, nothing. No one’s leaving.

- These children—these people—before here, who were they? Who are they now?

- Internment unwarranted, product of prejudice, intolerance, close-fisted greed.

- September 14, 1942. School opens for grades one through seven, 1,001 students.

- No classrooms. Relegated to community halls, cavernous spaces. Students sit on floors.

- Winter falls hard. No heat.

- September 17, 1942. Classes are closed for an unspecified period of time.

- October 9, 1942. School for lower grades once more in session.

- October 15, 1942. School opens for grades seven to twelve: 1,376 students.

- Days pass. Tensions build. There is much more to this story.

Focus, now, on bright spots.

Classrooms were, finally, moved to restructured barracks.

Resourceful teachers are respected and admired for their dedication.

Determined parents align in respect for education.

Reading:

- Old newspapers donated from far-flung towns.

Writing:

- Letters to classmates and friends now distant.

Arithmetic:

- Counting days of homelessness until . . . when?

- Counting miles to home. Will we ever return?

- Counting steps toward a nebulous future, seemingly fleeting, just out of reach.

Chasing the future like kick the can.

~ ~ ~

*Note of interest: If you’d like to know when yellow became the standard color for school buses, you’ll find that here. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/history-how-school-buses-became-yellow-180973041/

Good to know: The schools of Bainbridge Island, Washington, sent textbooks with their departing students.

More to know: “Makeshift classrooms were often overcrowded. Clifford D. Carter, superintendent of Heart Mountain Schools, noted that classroom occupancy exceeded Wyoming standards by 80 to 100 percent, with one 20′ by 100′ barrack classroom reporting 203 students.” What “Back to School” Looked Like in World War II Concentration Camps – Densho: Japanese American Incarceration and Japanese Internment.