WHY HISTORICAL FICTION?

I recently happened upon a blog series, The Problem with Historical Fiction, by Carolyn Hughes and, curious, I read the three installments. Not, as some might think, because I hoped to find there really is no problem. For a fact—there is. Life is a series of complications; they come in all sizes. Specifically, though, what are the issues addressed by Ms. Hughes?

- Is historical fiction a worthwhile endeavor for a writer?

- Is it worthy of your attention as a reader?

At the top of Ms. Hughes’ list of problems—and note, I’m not saying I agree—is that, while we might accurately portray the natural and human-built features of an era, we cannot presume to know the inner terrain, the thoughts and emotions, of our fictional characters.

Ms. Hughes refers to a perspective on history attributed to Napoleon Bonaparte. After sifting through sources (see all, below) for an exact wording, I selected, from the PBS film, Napoleon,

“History is a set of lies that people have agreed upon.”

So, some have termed history to be “a lie.” This might lead us to the conclusion that historical fiction is a fabrication of lies told about a lie. But what is fiction if not fictitious?

According to Merriam-Webster— “Fiction: ‘Specifically: an invented story.’”

Carolyn Hughes, in The Problem with Historical Fiction, states, “All fiction is an illusion created by the writer’s imagination. Yet historical, no less than contemporary fiction, must be sustained by a foundation of fact, creating a sense of ‘authenticity,’ in order for readers to accept the illusion as temporary reality.”

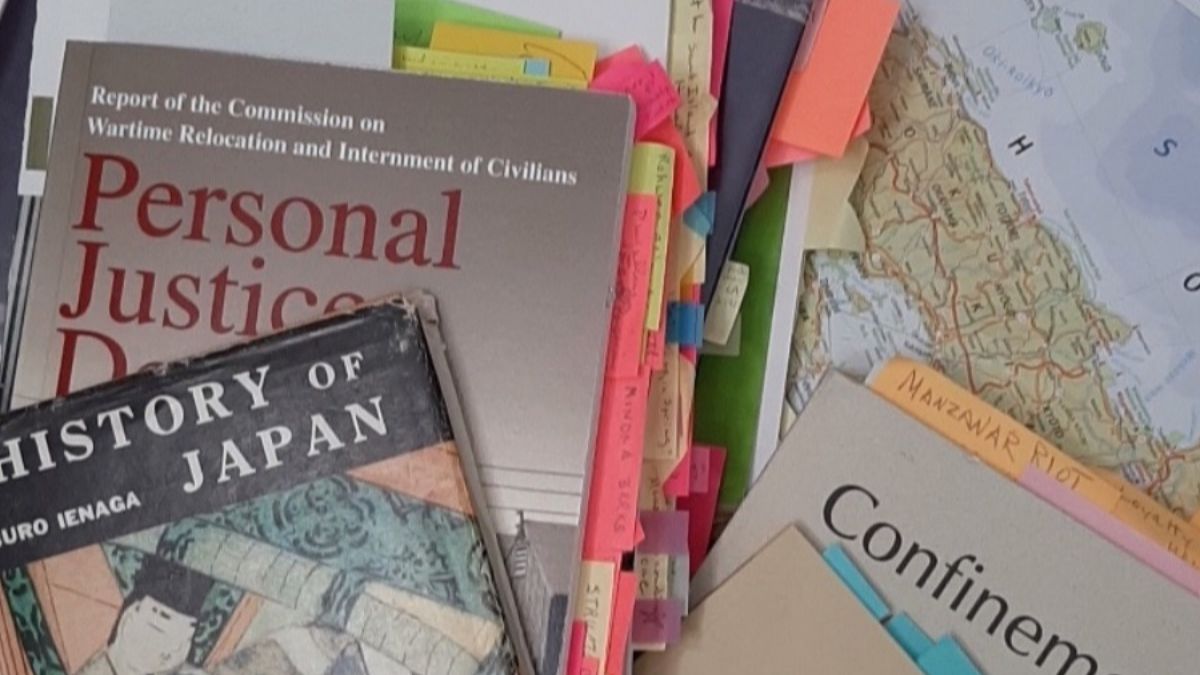

In my own work, I strive to ground the story in fact: dates, seasonal conditions, models of equipment and automobiles, clothing, what is eaten, what is read.

Zeroing in on seasonal conditions, when drafting a Bainbridge Island, Washington, winter scene, I hoped to portray the weather exactly as it was on the dates I had pinpointed. Temperature. Humidity. Wind speed. Precipitation.

Looking for those dates, I searched old almanacs, digitalized versions of Seattle’s Post-Intelligencer, Milly and Walt Woodward’s storied newspaper, The Bainbridge Island Review, and I learned something wholly new to me. Public view of weather maps and forecasts of atmospheric conditions was banned following the Pearl Harbor attack in 1941.

“In the first days after the attack, the publication of weather data west of the Cascades and Sierra Mountains along the West Coast was restricted by the U.S. Army . . . Then offshore weather reports and forecasts were curtailed on Dec. 13. By a week following the attack, restrictions on public weather information would expand to cover the nation.” Most were lifted on October 31, 1942.

In Part Two, Carolyn Hughes points to a situation I find challenging in my own writing. “The ‘facts’ of history are continually changing, as the latest research inevitably reveals previously unknown information and offers new interpretations of historical truths.”

Too often, several chapters of a manuscript based on previous knowledge or research have been drafted when the writer learns a new truth. For example, a commonly accepted image of internment camps features barbed wire fences and boundaries studded with guard towers staffed by soldiers with rifles. From these towers, we have read, search lights strafed the enclosure at random throughout the night. However, in the case of Minidoka, while the camp was originally surrounded by barbed wire, all but one stretch along the highway was later removed, as it was shown to be unnecessary amid the desolation of the site. Guard towers were framed but, due to supply shortages, equipment needed for electrification could not be obtained and the towers were not fitted with search lights.

We know this to be true, internees were imprisoned not only by fences and armed guards. They were constrained also by the terrain surrounding the camp, harsh weather, checkpoints, and curfews, but primarily by the color of their skin. Where could they go, and go unnoticed?

A condition of internment: Only what they could carry. A condition of exit: What they could not leave behind. To think of such injustice, such inhumanity, never fails to lay me low.

The majority of those imprisoned did not want to simply leave. They wanted to return to homes from which they were now barred. Return to their businesses, jobs, schools, churches. Their communities. Their responsibilities. They needed to go home.

The truth is never false but, perhaps, yet unrevealed. With integrity, historical fiction plays a role in keeping alive the quest for truth.

What are your thoughts on how imaginative historical fiction authors should allow their stories to be? Do you prefer books that hew closely to official records, with only dialogue improvised? Or are you comfortable in allowing a great deal of room in the telling of a story from another era?

************

The Problem with Historical Fiction, by Carolyn Hughes November 2, 2016, November 9, 2016; November 16, 2016

1 – The problem with historical fiction (I) – Carolyn Hughes (carolynhughesauthor.com)

2 – The problem with historical fiction (II) – Carolyn Hughes (carolynhughesauthor.com)

3 – The problem with historical fiction (III) – Carolyn Hughes (carolynhughesauthor.com)

How the attack on Pearl Harbor led to ban on US weather data (foxweather.com)

PBS – Napoleon: The Man and the Myth

“‘History is a set of lies that people have agreed upon,’ Napoleon said. ‘Even when I am gone, I shall remain in people’s minds the star of their rights, my name will be the war cry of their efforts, the motto of their hopes.’”